Explore the fraud problem

On this page

Let’s unpack what fraud is, why it’s such a challenging problem and why we need to do our best to counter it.

What is fraud#

The Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework defines fraud as ‘dishonestly obtaining (including attempting to obtain) a gain or benefit, or causing a loss or risk of loss, by deception or other means’.

A benefit or loss is not restricted to a material benefit or loss, and may be tangible or intangible. A benefit may also be obtained by a third party.

There are many ways people commit fraud against the Commonwealth. One way is if they follow practices or make decisions that are fraudulent when recruiting or contracting.

Other times, fraud happens when people steal, misuse or misdirect:

- cash, credit cards, payroll, entitlements, travel vouchers, invoicing or procurement

- revenue, royalties or fees

- payments or services, such as by claiming them fraudulently

- facilities, vehicles, equipment and other physical assets, or when they damage those assets.

People also commit fraud against the Commonwealth if they steal, misuse or disclose:

- citizen or official program information

- employee information, intellectual property or other official information.

Internal fraud is a form of corruption. It happens when officials commit fraud against the entity they work for.

Fraud requires intent. It involves more than carelessness, accident or error. When intent cannot be shown, an incident may be non‑compliance rather than fraud.

Explore the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework to learn more about the Commonwealth’s definition of fraud.

What fraud looks like#

Cases of fraud against government programs show that fraudsters have common traits:

- Deception – making others believe something that is not true.

- Recklessness – acting without care, responsibility or regard to the consequences of their actions (this includes disregarding the harm caused to others)

- Concealment – preventing actions from being seen or known about

- Fabrication – inventing or producing something that is false.

- Impersonation – pretending they are another person or entity.

- Coercion – influencing, manipulating or bribing another person to act in a desired way.

- Exploitation – using something for a wrongful purpose.

Some studies have analysed the characteristics of people who commit fraud to build a profile of a typical fraudster and identify risk profiles for individuals.

The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners found it is 13 times more common for an employee to commit fraud compared to an owner or executive. However, the median loss through fraud committed by owners or executives is 10 times larger than fraud committed by employees.

More importantly, these studies also show us that all individuals are capable of committing fraud. As the case study demonstrates, with the right mix of pressure, opportunity and rationalisation, even trusted colleagues and friends can be tempted to commit fraud.

Use the Fraudster Personas to understand different methods individuals use to commit fraud and how you can stop them.

Use the Case Study Register to find more examples of fraud.

Case study #1#

A Melbourne pharmacist was sentenced to 2 years in jail after an investigation proved he had defrauded the Australian Government’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) of roughly $110,000 between 18 August 2019 and 20 September 2019.

The pharmacist submitted 76 false PBS claims, using his position as an approved pharmacist and ‘intimate knowledge of the PBS claim system’ to make fraudulent claims.

The offences came to light when a supplier of pharmaceutical products that were the subject of his claims notified the Commonwealth through an online Department of Health and Aged Care tip-off form.

Why people commit fraud and the drivers for fraud#

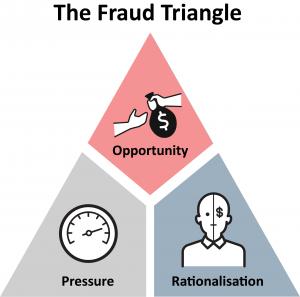

Criminologist Donald R. Cressey identified three conditions that must be present for an ordinary person to commit fraud.

Pressure

People are pressured to commit fraud for many different reasons. For example, they could be:

- lured by greed and easy financial gain

- pressured by negative influences such as loss of employment or status, gambling addictions, health problems or crippling debts.

Opportunity

People must have the opportunity to commit fraud. This is generally because an entity has weak controls such as a lack of oversight. Often the fraud starts small and then increases once the opportunity is confirmed.

Rationalisation

People must be able to rationalise the act of fraud in their own mind. Most people who commit fraud are first-time offenders with no criminal history.

Therefore, they find a way to make it okay to perform the fraudulent act. Such rationalisations include:

- 'I’ll pay it back later.'

- 'No one will even notice it’s gone.'

- 'I deserve it.'

- 'I pay enough tax.'

- 'I’m doing it for my family.'

The specific rationalisation may change or become less relevant as the fraud continues or increases. Sometimes, the rationalisation is replaced with increasing feelings of guilt and shame.

Why fraud is such a challenging problem#

Fraud is often underestimated and unchecked

It is a hidden threat that is deliberately concealed and often overlooked by its victims. Fraud and error, including unreported fraud, could be costing the Commonwealth as much as $100 million per day. This cost is equivalent to funding the Commonwealth’s Drought Community Support Initiative for more than a year.

Fraud is common

According to the Australian Institute of Criminology, there are tens of thousands of instances of reported fraud and corruption against the Commonwealth each year. The prevalence of fraud makes it a challenging and costly problem for governments to deal with.

Those who commit fraud are diverse, creative and adapt quickly

Fraudsters range from people taking advantage of opportunities to those who actively look to exploit government programs. Fraud is a profession for some. Their job and expertise is to examine government programs and find creative ways to exploit those programs.

Serious and organised crime is involved

Criminals use advanced approaches and scheme with professionals, such as accountants, to exploit multiple government programs.

Fraud is becoming increasingly complex

Criminals and scammers are adopting new technology and more advanced methods to commit fraud.

The impacts of fraud, why we should care and how it affects us#

Fraud reduces the government’s capacity to deliver services and support for all Australian citizens. Every dollar lost to fraud is a dollar not invested in Australia’s healthcare system, education system, economy or public safety.

Being a victim of fraud can be a traumatic experience. Those who rely on government services such as the elderly, the vulnerable, the sick and the disadvantaged are often the ones most harmed by fraud.

Fraud can have a devastating and compounding effect on these victims. It can amplify the disadvantage, vulnerability and inequality they suffer. Fraud can also cause lasting mental and physical trauma for victims and irreversible impacts for families and communities.

Fraud reduces public trust in government, undermines Australia’s institutions and can damage our industries, our security and our environment.

Read more about the impacts of fraud.

Case study #2#

A Queensland man has pleaded guilty to 5 offences of defrauding the Commonwealth of $94,777.82 by fraudulently claiming disaster recovery payments. He was sentenced to 4 years’ imprisonment, with a non-parole period of 21 months. The court also made a reparation order for the outstanding debt of $93,641.10.

Between 11 May 2017 and 16 May 2019, the man defrauded Services Australia (Centrelink) of 116 payments of social security benefits paid in relation to fraudulent claims for the Australian Government Disaster Recovery Payment (AGDRP).

He created 66 false identities and assumed the identities of 17 existing Centrelink recipients to submit the fraudulent AGDRP claims. He also assumed the identities of 11 existing Centrelink recipients for the redirected payments.

At the time of his arrest on 17 May 2019, he was found in possession of 289 items of identification information in the names of identities other than his own. These identification documents were obtained through his employment at Sunshine Coast College of Management.

Read more at CDPP successfully prosecutes fraudulent claims for Queensland disaster relief payments.