How to design fraud and corruption controls

Table of contents

Managing risks like fraud and corruption is a professional exercise that requires:

- knowledge of different methods and enablers,

- risk management processes, and

- discrete business processes and systems.

These components are also necessary for discovering insights into problems, defining areas to focus on, developing potential solutions and delivering solutions that work.xiii

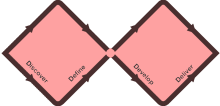

Figure 1 – The UK Design Council’s Double Diamond design process

The two diamonds represent a process of exploring an issue more widely or deeply (divergent thinking) and then taking focused action (convergent thinking).

Discover – The first diamond helps people understand, rather than simply assume, what the problem is. It involves speaking to and spending time with key stakeholders.

Define – The insight gathered from the discovery phase can help you to define the challenge in a different way.

Develop – The second diamond encourages people to give different answers to the clearly defined problem, seeking inspiration from elsewhere and co-designing with different stakeholders.

Deliver – Delivery involves testing out different solutions, rejecting those that will not work and improving the ones that will.xiv

Applying the principles of co-design when developing controls and control frameworks will enable you to:

- cultivate positive and productive relationships with business stakeholders, leading to more informed, better designed, proportionate and cost-effective controlsxv

- encourage greater buy-in, sense of ownership and follow-through from stakeholders in addressing the identified gaps in their control environment.

The following principles of co-design have been adapted from the principles developed by the NSW Council of Social Services:

-

Outcomes-focused

Co-design can be used to create, redesign or evaluate controls with an aim to achieve specific outcomes. Also, because controls are developed with stakeholders, they can be more rapidly developed, tested and measured. Controls can also be applied or scaled with an appropriate understanding of the risks and the business objectives, which can help with measuring improved result or impact.

-

Inclusive

The process of co-designing effective controls involves critical stakeholders from the point of discovering and defining the problems through to developing and testing solutions. It utilises feedback, advice and decisions from participants with different kinds of knowledge (professional and specialist expertise).

-

Participative

Co-design involves open, empathetic and responsive conversations and activities where dialogue and engagement generate new and shared understanding throughout the process. The understanding gained through this participative process is then used as the basis for co-designing workable solutions.

-

Respectful

The expertise, perspectives and input of all participant is valued. Negotiations are undertaken in a respectful way, with the focus remaining on shared challenges and achievement of common objectives.

-

Adaptive

Co-design can often be an experimental process aiming at innovation and workable solutions. Feedback loops, learning, iteration, and trial and error are all part of the process. Assumptions, ideas and proposed solutions are tested and challenged by participants. This critical and adaptive approach to control design helps to fine-tune them prior to implementation. It also helps to develop clear metrics for evaluating control effectiveness, which can later be used for assurance purposes post-implementation.

The technical requirements for each control will be highly dependent on the type of control and its intended purpose. The following 12 technical considerations are a helpful reference when designing fraud and corruption controls:xvi

-

Relevance

How relevant is the proposed control to the risks being mitigated? For example, a quality assurance process may only check that processes had been completed, not whether the claims processed are actually fraudulent.

-

Coverage

To what extent will the proposed control address all significant risks? For example, do fraud and corruption detection algorithms cover only some of the risks across a process?

-

Timeliness

How long will it take for the proposed control to respond to negative events and minimise adverse consequences? For example, sending a letter to a vendor about bank account changes may not allow for timely action to stop fraudulent payments.

-

Reliability

To what extent can the proposed control be relied upon to perform its intended function without failure? For example, are employees sufficiently trained to identify fraudulent evidence?

-

Discretion

Will there be a level of discretion or subjectivity in the application of the proposed control? For example, can the application proceed without the user uploading mandatory evidence to the online form?

-

Segregation

Will there be segregation between the proposed control and those subject to the control? For example, will an employee subject to the control have the ability to affect its operation?

-

Independence

Will the proposed control’s execution depend on resources that might not always be available? For example, will the detection control rely on data or staffing resources that might not always be available?

-

Integration

To what degree and manner will the proposed control be integrated with other controls? Will it support other controls? For example, will a new automated decision-making workflow ensure decisions are made in line with defined authorisations/delegations?

-

Automation

Will the proposed control be automated or applied by people? If applied by people, how will you know they will apply the control consistently or correctly? Will automated controls still be reliant on some human input, which might allow for errors?

-

Adaptability

How adaptable will the proposed control be to fluctuating volumes of activity or changing environments? For example, will the control still be applied during peak periods even if it affects business or system performance?

-

Traceability

To what extent will the proposed control be traceable, allowing it to be verified? For example, will the necessary data be available to allow you to confirm if monthly reconciliations are actually performed?

-

Validation

To what extent will the proposed control be tested and reviewed against the risk? For example, how regularly will segregation of duties controls be audited or monitored?

The SMART principle for designing controls

The SMART principlexvii is an example of what to consider when co-designing controls with stakeholders:

Specific

The control should have a clear and concise objective, be well defined and clear to anyone with a basic knowledge of the work. Consider who, what, where, when and why.

Measurable

The control and its progress should be measurable. Consider:

- What does the completed control look like?

- What are the benefits of the control and when they will be achieved?

- The cost of the control (both financial and staffing resources)

- How do the costs balance against the benefits?

Achievable

The control should be practical, reasonable and credible considering the available resources. Consider:

- Is the control achievable with available resources?

- Does the control comply with policy and legislation?

Relevant

The control should be relevant to the risk. Consider:

- How does the control modify the level of risk (through impacting the causes and consequences)?

- Is the control compatible with the organisation’s objectives and priorities?

Timed

The control should specify timeframes for completion and when benefits are expected to be achieved.

The SMART approach will help you describe what each control actually does to mitigate the risk and how it will operate. You should also be able to describe what the control does not do in relation to mitigating the risk. By being specific about the effect, you will be able to design treatments that are:

- Easier to explain and negotiate – there will be a clear and specific purpose (relevant to the risk)

- More relevant – it will be clearer how the control modifies the risk

- Better designed – there will be clearer requirements and therefore it will be easier to implement

- More targeted – it will be clearer where, when and to whom the control should apply

- Proportionate – there will be a specific intent to the control, and therefore it will more likely stay compatible with the organisation’s objectives and priorities

- Easier to measure if they are working effectively – it will be clearer how the control is designed to work

- Easier to measure their value – it will be clearer what affect/change the control is expected to deliver and when the benefits are expected to be achieved.

In our Fraud Risk Assessment Leading Practice Guide we suggest risks should be articulated using active voice through the structure of Actor, Action, Outcome. We can apply a similar structure for articulating controls to reinforce key requirements, such as an active agent (capable guardians from Routine Activity Theory), a specific function and objective, and a specific effect. For example:

- Active agent – Who or what applies the control? Is this a person or a system?

- Action – What does the control do?

- Outcome – What is the result or intention?

Examples:

- Processing officers (Active agent) cross-check application details with income data from the Single Touch Payroll (Action) to verify eligibility for payment (Outcome)

- System user permissions (Active agent) enforce separation of duties (Action) so a single user cannot execute all functions (Outcome)

- Fraud Awareness Training (Active agent) provides relevant information to staff (Action) to help them prevent, detect and report fraud (Outcome)

The Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Policy notes that the actions taken by entities to manage fraud and corruption risk should be applied in a way that is proportionate to the level of risk involved in the organisation’s activities and operating context. The same expectation applies to the development of individual controls and control frameworks.

This involves striking the right balance between the cost of controls and the benefits they are expected to yield. The cost of control should be measured based on fixed and non-fixed costs (e.g., dedicated resources, operational costs, costs of maintaining the information system, etc.) as well as external costs (e.g. costs to citizens or business). This cost should be compared to that of managing residual risk.

Another factor to consider is the degree of control effectiveness that is necessary to appropriately mitigate the probability, frequency, duration or impact of fraud and corruption risk. In general, the greater the effectiveness of a control, the greater the cost. Alternative solutions should always be considered that may achieve a superior cost/benefit ratio.xviii ;This is where a co-design approach can be particularly valuable.

In order to accurately weigh the costs and benefits, it is important to consider all the potential impacts of fraud and corruption, including the second and third order impacts.

The common impacts of fraud and corruption:xix

Human impact

Fraud and corruption in the public sector are not victimless crimes. Fraud and corruption can be a traumatic experience that often causes real and irreversible impacts for victims, their families, carers and communities.

Financial impact

It is estimated that losses to fraud and error can average between 3% and 5.95% of government outlays. The majority of fraud is hidden and undetected and can be difficult to categorise.

Environmental impact

Fraud and corruption can lead to immediate and long-term environmental damage through pollution and damage to ecosystems and biodiversity. It can also result in significant clean-up costs.

National security impact

Fraud and corruption can compromise national defence and security, putting citizens at risk. Fraud against government programs can be used to fund organised crime groups and terrorism, potentially leading to further crime and terrorist attacks.

Physical impact

Fraud and corruption can result in people having unnecessary or unsafe medical procedures, expose people to hazardous substances or environments, lead to vehicles or airplanes crashing through faulty parts or maintenance, and lead departments to rely on faulty or unsafe safety equipment or faulty infrastructure.

Government outcomes impact

Fraud and corruption compromise the government’s ability to deliver services and achieve intended outcomes. Money and services are diverted away from the intended targets and the services delivered can be substandard, unsafe or wasteful.

Reputational impact

Fraud and corruption can affect any organisation. However, when it is handled poorly, fraud and corruption can result in an erosion of trust in government and industries, and lead to a loss of international and economic reputation.

Industry impacts

Fraud and corruption can result in distorted markets where dishonest actors obtain a competitive advantage and drive out legitimate businesses.

Developing an investment case for fraud and corruption control activities

As noted above, fraud and corruption can cause serious harm to government programs, industries, businesses and everyday Australians. However, due to the hidden nature of fraud and corruption, there is often limited evidence to support the vital investment needed to prevent these crimes. Furthermore, the benefits achieved through investment in counter fraud and anti-corruption activities can be hard to demonstrate. How do you quantify what you prevented? And what if your investment leads to you finding more fraud or corruption? Is that a good thing?

Our Counter Fraud Investment Cases Leading Practice Guide, developed in collaboration with Deloitte, provides practical steps for developing a business case for investment. This helps you communicate the problem to senior leaders, educate them on the financial and non-financial benefits of prevention, and make a strong case for investing in effective counter fraud or anti-corruption measures and resources.

Specifically, this guide takes you through the 5 practical steps for developing an investment case:

Step 1 – Confront challenges and resistance: discover what to do when evidence is limited, benefits might be hard to explain and costs don’t seem worth it. Also explore some common misconceptions you may be faced with.

Step 2 – Understand and define your context: outline the need for counter fraud investment, collect the evidence you can to support it, estimate the financial cost and potential savings, understand the non-financial impacts of fraud and anticipate questions from executives.

Step 3 – Develop a strategy: determine your organisation’s current counter fraud maturity and risk appetite, the next step in your counter fraud journey and the short-term and long-term investment goals.

Step 4 – Tell your story: share all of the above in a clear, simple and compelling story.

Step 5 – Communicate your value: communicate the value of investment and demonstrate your impact.

While this guide is written for the counter fraud context, the principles and practical steps are relevant to anti-corruption investment cases.