Why people commit fraud or act corruptly

Table of contents

“Incentives are what drive human behaviour. Understanding incentives is the key to understanding people. Conversely, failing to recognize the importance of incentives often leads us to make major errors.”

- Shane Parrishiii

When thinking about why people commit fraud or act corruptly we should always think about the power of incentives. Sometimes incentives can motivate people to make undesirable choices or behave in ways that lead to unintended negative outcomes. These are known as perverse incentives.

A classic historical example is from the British government who, in an attempt to reduce the number of cobras in Delhi, established a reward program for people to hand in dead cobras. While initially successful, it ultimately resulted in a cottage industry of cobra breeders who began collecting a handsome income from the program. After scrapping the program, the breeders set their snakes free, which ultimately resulted in more deadly cobras roaming around Delhi than before.

Understanding the power of incentives enables us to better influence undesirable behaviour or choices by adjusting incentives so that they align to a desired goal, e.g. to encourage compliance or ethical behaviour.

Case study – Unrealistic sales quotas

In an attempt to increase sales, Wells Fargo, a major financial institution in the US, set aggressive sales targets and bonuses for their staff, which included unreasonable daily quotas for the products sold to new and existing customers – at one point they were expected to sell 20 products a day.

This incentivised bank staff to achieve these targets by any means necessary, resulting in around 2 million fraudulent and duplicate bank and credit card accounts being opened and operated by bank staff without the customers’ knowledge or permission.

Ultimately, Wells Fargo agreed to pay US$185 million in settlements to US regulators.iv

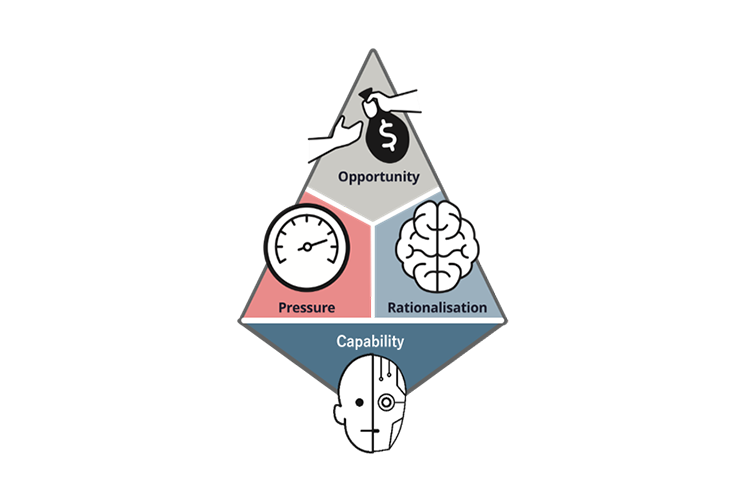

The ‘fraud triangle’ is a model developed by Criminologist Donald R. Cressey, which is commonly used to explain why an individual might commit fraud. It describes three key components that contribute an individual’s decision to do something fraudulent: opportunity, pressure and rationalisation. The later expanded fraud diamond model adds the element of capability, which are the personal abilities that play a role in whether fraud can occur.

With the right mix of pressure, opportunity and rationalisation, anyone can be susceptible to committing fraud.

Opportunity

People must have the opportunity to commit fraud. This generally involves vulnerabilities in processes and systems that can be exploited for financial gain. Often frauds start small and then increase once the opportunity is confirmed.

Opportunity is the part of the fraud triangle that entities can most meaningfully influence through effective people, policy, process and technology controls.

Pressure

This can be described as the things that drive a person to commit fraud. Common examples include financial pressures, gambling addictions, substance abuse or simply a person’s greed or desire for financial gain. The growth in social media use has contributed to an increase in the prevalence of social anxiety and ‘status envy’. These problems can incentivise individuals to commit fraud in order to demonstrate a lifestyle of wealth and status.

Pressure to commit fraud is often driven by external forces and therefore is not always something that entities can influence. Pressure can also vary over time and otherwise trusted employees and suppliers can turn to fraud if their circumstances change. Assessing fraud and corruption risks can help entities identify areas susceptible to this pressure and mitigate risks by identifying and responding to behavioural red flags, such as gambling addiction, and through effective policy design and management practices, e.g. minimising incentives that may entice someone to commit fraud.

Rationalisation

This refers to a person’s justification for committing fraud. In simple terms, they find a way to make it okay to perform the fraudulent act. Such rationalisations include,

- “I’ll pay it back later”

- “I’m not hurting anyone”

- “I’m doing it for my family”

All humans are susceptible to biases. Studies have shown that biases are predictable and can be leveraged to improve situational crime prevention.v For example, people who engage in fraud or corruption are generally rational actors and their goal is to minimise effort and risk while maximising gain.vi This means in many circumstances we can reduce a person’s ability to rationalise their actions, including by influencing their beliefs and perceptions about the risks vs benefits of committing fraud or acting corruptly. However, there are limits to what we can influence. For example addiction-driven crimes, where desperation or withdrawal can override clear-headed math.

The Centre’s Fraud Messaging Toolkit provides practical advice on how to use messaging as an effective and low-cost method for reducing fraud. Messages intending to deter fraud can be included in government announcements, communications, press releases, websites and application forms. These messages are designed to make someone feel they are either likely to be caught if they commit fraud or the consequences of being caught will outweigh any benefit they might get through fraud.

Capability

Not everyone will have the capability to commit fraud. Many frauds would not occur without the right person with the right ability to carry out the fraud. Having the means to commit the fraud, such as being in a position of authority, is key.

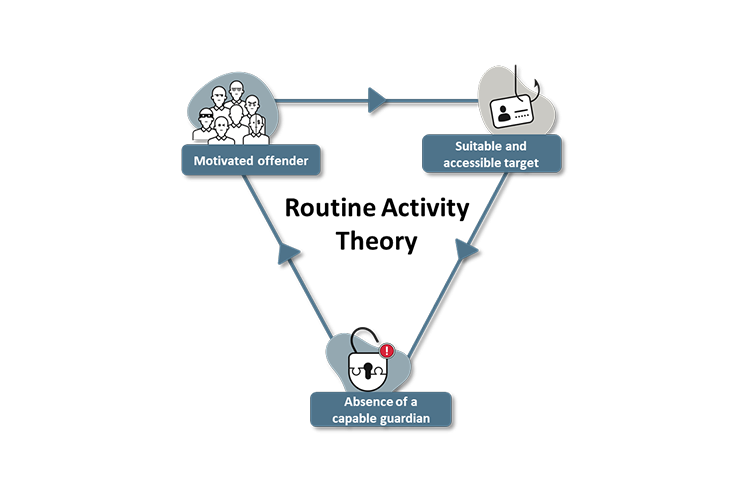

Cohen and Felson's routine activity theoryvii and Eck's crime triangleviii look at crime from an offender's perspective. Similar to Cressey's fraud triangle, we can use these models to identify and evaluate the elements that come together for crime to occur. Routine activity theory states that a crime occurs when the following three elements come together in any given space and time:

- an accessible target

- the absence of capable guardians that could intervene

- the presence of a motivated offender.

For example, a wallet sitting on the dashboard of a car with its windows down is an accessible target. With no one around to watch over the wallet means the absence of a capable guardian that could intervene. All that’s required for crime to occur in this situation is the presence of a motivated offender.

Routine activity theory provides a framework within which to prevent crime through altering at least one of these elements (the offender, the target or the presence of capable guardians). The most effective crime prevention strategies will focus on all three of these elements.

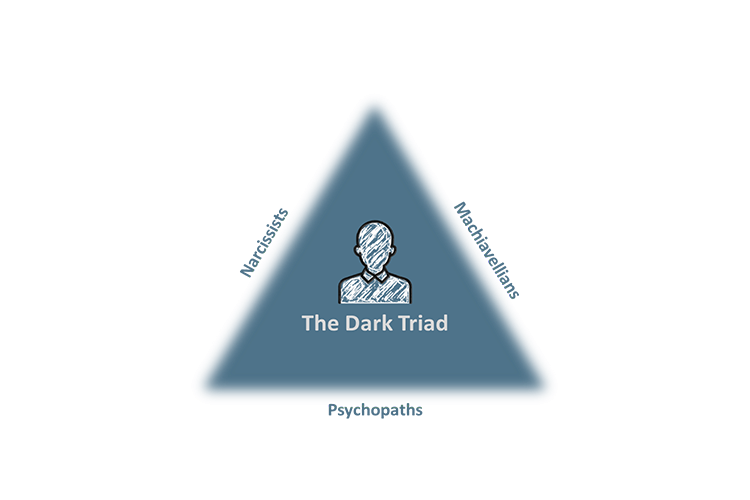

It is also important to acknowledge that a percentage of the population have traits that are known as the Dark Triad: psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism.ix These traits affect different parts of the unethical decision-making process.

- Narcissism motivates individuals to act unethically for their personal benefit and changes their perceptions of their abilities to successfully commit fraud or act corruptly.

- Machiavellianism motivates individuals not only to act unethically, but also alters perceptions about the opportunities that exist to deceive others.

- Psychopathy is a disorder marked by deficient emotional responses, lack of empathy, and poor behavioural controls, commonly resulting in persistent antisocial deviance and criminal behaviour.

A key takeaway is that individuals with dark triad traits may commit fraud or act corruptly without any pressure or the need to rationalise the act – they only need opportunity. They also have the capability (manipulation abilities etc.) to commit and conceal fraud or corruption. Moreover, the presence of corporate psychopaths may even create the conditions for fraud or corruption within an organisation.x

It is therefore important to have strong systems of control in place to minimise the opportunity for those with intent to commit fraud or act corruptly.

Countering the Insider Threat

The insider threat poses an immense risk for both Australian Government and non-government entities. Ensuring your entity has an insider threat program in place is essential to also mitigating fraud and corruption risks.

The Guide to Countering the Insider Threat, developed in collaboration by AGD, ASIO, ACLEI, ASIC, DAFF, ONI and Services Australia, is designed to support Australian Government entities to consider what practices and procedures should be in place to identify insider threats, and support workforces to report any suspicious activity that could pose a threat. This includes ensuring processes are set up to help personnel understand their role in protecting government information and upholding integrity.