1. Introduction

Table of contents

Overview

Part 1 of the Leading Practice Guide sets out the basics of the fraud problem faced by the Australian Government and outlines the legal and practical need for fraud risk assessments. This part also includes information on:

- a conceptual framework for fraud risks against the government, including fraudster motivation and behaviours

- the legal framework for fraud risk assessments under the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework

Assessing fraud risks helps officials make good decisions. Knowing where you are vulnerable also helps officials to more effectively prevent fraud and reduce its impacts.

Fraud is a serious, underestimated and often unchecked problem that directly undermines the goals and reputation of the Australian Public Sector. Every Australian Government entity is exposed to fraud of some form, but because it is usually hidden from sight, constantly changing and not well understood by most people, the risks and impacts of fraud are often underestimated and overlooked. If left unchecked, fraud can seriously harm Commonwealth programs, officials, service providers and members of the public.

Fraud against Australian Government entities is driven by many factors, including vulnerabilities in policies, processes and systems that enable opportunistic individuals to take advantage. Fraud is also a profession for capable and committed criminals who actively look to exploit the services that many Australians rely on for their own dishonest gain.

Fraud risk assessments shed light in areas that might be vulnerable to this type of exploitation. This ultimately helps officials better understand the risks to their programs and functions and enables them to make better decisions about how to manage them.

Fraud is a specialist area of risk management and a quality fraud risk assessment is not a quick and simple process. It is a professional exercise that requires a combination of:

- knowledge about fraud methods and enablers

- risk management policies and processes

- business processes and systems.

Accurately assessing fraud risks, and making good decisions based on the results, usually requires coordination and collaboration across multiple business areas.

Fraud risk assessments

The purpose of this guide is to provide Fraud Control Officers with principles and methods which have been taken from leading fraud risk assessment practices across sectors. Officers can then apply or adapt these methods to suit their individual circumstances. The guide will also help fraud specialists, government officials (including policy designers) and senior leaders better understand the fraud risk assessment process and how these assessments can benefit their entity. In addition to this, the guide provides some high-level direction on other functions such as enterprise-level risk assessments and strategic fraud risk profiling.

Specifically, the guide will assist entities to:

- understand the purpose and objectives of a fraud risk assessment

- develop an understanding of how someone could defraud their entity

- identify programs and functions that are at higher risk of fraud, helping prioritise further assessment

- understand and apply the series of interrelated steps involved in a fraud risk assessment

- co-design solutions with stakeholders to effectively treat fraud risks

- continue to build knowledge and improve capability, leading to compounding value for entities.

The Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework defines fraud as ‘dishonestly obtaining (including attempting to obtain) a gain or benefit, or causing a loss or risk of loss, by deception or other means’.

Common areas of fraud risk within the Australian Government include:

|

Corporate Functions |

|

|

Policy and Program Functions |

|

Tip: Fraud requires intent. It requires more than carelessness, accident or error. When intent cannot be shown, an incident may be non-compliance rather than fraud.

A benefit is not restricted to a material benefit, and may be tangible or intangible, including information. A benefit may also be obtained by a third party. It may also include lost access rights, opportunities for employment or harm to others. Similarly, a loss is not limited to only meaning a financial or tangible loss. It may also include lost access rights, opportunities for employment or harm to others.

Fraud can also include some forms of corruption, particularly where a party obtains a benefit or the Commonwealth incurs a loss; for example, collusion between a Commonwealth official and a contractor.

It is helpful to picture fraud sitting on the end of a compliance spectrum. While most people in society are honest and wilfully comply with rules and obligations, it is also important to accommodate for the proportion of people who do not comply, including a small number who wilfully commit fraud. Fraud risk is therefore a business problem which is mitigated by maintaining and increasing compliance on one side and reducing the opportunity for fraud on the other.

The diagram shows compliance, non-compliance and fraud on a spectrum. Most people on this spectrum will comply with rules and obligations and should be enabled and rewarded to do so. Some people will not comply with rules and obligations (non-compliance), which should be detected and deterred with the aim of encouraging and supporting future compliance. At the extreme end of the spectrum a small number of people will act dishonestly and deceive for their own benefit, and in these cases, appropriate fraud controls should seek to investigate and disrupt fraudulent behaviour.

End of alternative text

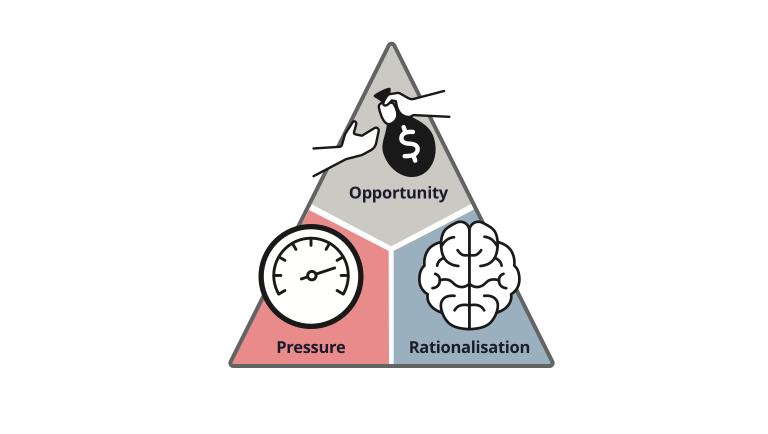

The ‘fraud triangle’ is a model which is commonly used to explain why an individual might commit fraud. It describes three key components that contribute an individual’s decision to do something fraudulent: opportunity, pressure and rationalisation.

With the right mix of pressure, opportunity and rationalisation, even the people we trust can be tempted to commit fraud.

The image shows a triangle with the three components that contribute an individual’s decision to do something fraudulent: opportunity, pressure and rationalisation.

End of alternative text

Opportunity

People must have the opportunity to commit fraud. This generally involves vulnerabilities in processes and systems that can be exploited for financial gain. Often frauds start small and then increase once the opportunity is confirmed.

Opportunity is one part of the fraud triangle that entities can meaningfully influence through effective people, policy, process and technology controls. Fraud risk assessments are critical to achieving this.

Pressure

This can be described as the things that drive a person to commit fraud. Common examples include financial pressures, gambling addictions, substance abuse or simply a person’s greed or desire for financial gain. The growth in social media use has contributed to an increase in the prevalence of social anxiety and ‘status envy’. These problems can incentivise individuals to commit fraud in order to demonstrate a lifestyle of wealth and status.

Pressure to commit fraud is often driven by external forces and therefore is not always something that entities can influence. Pressure can also vary over time and otherwise trusted employees and suppliers can turn to fraud if their circumstances change. Assessing fraud risks can help entities identify areas susceptible to this pressure and mitigate risks by identifying and responding to behavioural red flags, such as gambling addiction, and through effective policy design and management practices, e.g. minimising incentives that may entice someone to commit fraud.

Fraud risk assessments help officials identify areas that are susceptible to pressures and opportunities that may lead to fraud.

Rationalisation

This refers to a person’s justification for committing fraud. In simple terms, they find a way to make it okay to perform the fraudulent act. Such rationalisations include:

- “I’ll pay it back later”

- “I’m not hurting anyone”

- “I deserve it”

- “I pay enough tax”

- “I’m doing it for my family”

Fraud risk assessments can help to identify opportunities to deter fraud by reducing a person’s ability to rationalise their actions. This can be achieved by increasing the perceived risk of getting caught, reducing the perceived benefit of engaging in fraud, and making people aware of the impact fraud has on others.

It helps to think like a fraudster when conducting fraud risk assessments, evaluating processes and examining the effectiveness of controls. Adopting an overly optimistic mindset can lead to an underestimation of fraud and its potential impact on government systems and programs.

The fraud risk assessment process should consider the common methods employed by fraudsters, and look for vulnerabilities in programs or functions that motivate and enable fraudsters. This will involve challenging assumptions to identify creative ways to circumvent controls just like fraudsters do.

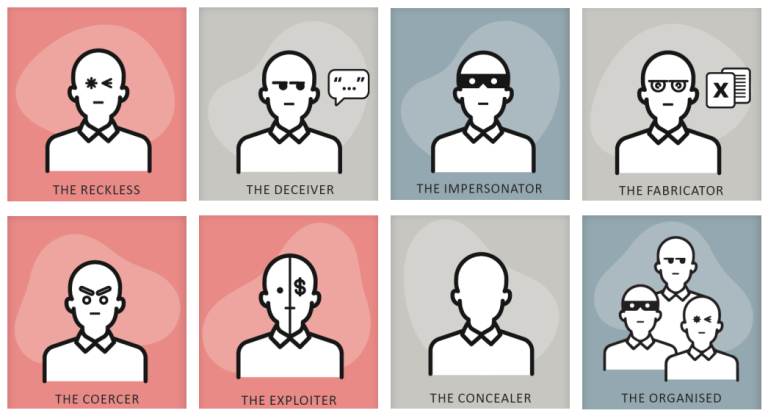

Using Fraudster Personas can help entities examine processes, systems and controls from the perspective of a fraudster. The Centre’s 8 Fraudster Personas align to common methods fraudsters use to target functions or programs, or to get around a control.

The images represent different Fraudster Personas: The Reckless, The Deceiver, The Impersonator, The Fabricator, The Coercer, The Exploiter, The Concealer and The Organised.

End of alternative text

Tip: Fraudsters often exhibit behaviours from several different personas. For example, they may deceive a public official, impersonate another individual, fabricate evidence and then conceal their activity.

For the purposes of this guide, ‘fraud risk assessment’ is defined as a standard business process which enables entities to identify, analyse, evaluate and treat fraud risks which may be inherent to their business functions. The process is not one activity, but a series of interrelated steps that periodically recur:

- Risk identification - There are different approaches to identifying fraud risk which are provided in this guide. However, they all fundamentally aim to articulate how fraud actors might apply known fraud methods against business processes. Once identified, fraud risks should be articulated in a concise and consistent manner.

- Risk analysis - This step involves documenting and analysing the different controls currently in place to mitigate the identified risks. The effectiveness of existing controls must be scrutinised in close collaboration with the business as not all will necessarily have a material effect on the risk. This step also involves estimating the level of the fraud risks based on their likelihood of occurring and their consequences if realised to then determine the level of risk.

- Risk evaluation - This involves fraud risk owners (see Section 2.4) evaluating whether fraud risks are within stated tolerance levels and what further action, if any, is required. This might involve doing nothing more than maintaining existing controls and monitoring the risk, through to developing new controls and changing business processes.

- Risk treatment - For those fraud risks which are outside stated tolerance levels, fraud risk owners must consider the most appropriate risk treatment options by balancing the potential benefits of new or enhanced controls against the costs and effort of implementation and administration of those controls.

Fraud risk assessments provide assurance that public funds are being managed in an accountable manner and that the potential harms of fraud are being actively mitigated. Importantly, the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires entities to establish appropriate systems of risk management and internal control. Consistent with the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework and the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy, fraud risk assessments should be an integral element of an entity’s governance and policy arrangements. These arrangements should prescribe how risks are reported and how risk management processes are embedded into key business processes.

The Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework is designed to operate in a way that recognises the different operating contexts of Commonwealth entities, and the different scale and nature of fraud and corruption risks that can result. This allows the officials responsible for managing risks of fraud and corruption relating to an entity to determine what are reasonable and appropriate mechanisms for that entity. What is reasonable and appropriate will vary based on the size and operations of an entity as well as the nature and complexity of an entity’s fraud and corruption risks.

Each accountable authority must establish a system of internal control for fraud and corruption that is fit for purpose to protect the entity from these risks. These decisions should be informed by an understanding of the fraud and corruption risks faced by an entity, and its appetite and tolerance for those risks, and be made and documented through the governance arrangements established to manage fraud and corruption risk within an entity.

Australian Government entities can have varying levels of capability maturity with regards to fraud prevention and conducting fraud risk assessments. This can be driven by factors such as entities’ relative levels of inherent fraud risk and executive commitment to fraud prevention activities. Entities should try to progressively mature their fraud risk assessment capabilities to ensure their processes are appropriate, cost-effective and proportionate with the entity’s risk profile.

Tip: Entities with programs that may carry inherently high fraud risks are encouraged to develop fraud risk assessment processes that are specific to these programs. It is particularly important for the fraud risk assessment process to be incorporated across a program’s lifecycle: from planning and design to implementation and delivery.

Refer to our Counter Fraud Investment Cases Leading Practice Guide or practical advice on seeking new investment and resources.