4. The fraud risk assessment process

Table of contents

Overview

Part 4 of the Leading Practice Guide sets out the process for fraud risk assessments, including 4 key steps:

- Identifying fraud risks

- Analysing fraud risks

- Evaluating fraud risks

- Treating fraud risks

When conducting fraud risk assessments, the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework encourages entities to consider the relevant recognised standards, currently the Australian/New Zealand Standard AS/NZ ISO 31000-2018 Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines and the Australian Standard AS 8001-2021 Fraud and Corruption Control. This guide describes methods and processes consistent with both the relevant standards as well as international and domestic leading practice approaches. Entities are also encouraged to consider their own risk management framework.

The fraud risk assessment process is broken down into the following four key steps:

- Risk identification

- Risk analysis

- Risk evaluation

- Risk treatment.

Four key steps

Identifying fraud risks should be a creative process. There can be a temptation to be defensive and argue away risks, but this is a process of finding out what could go wrong – thinking like a fraudster. Identifying fraud risks should be viewed as a positive outcome. Entities may also benefit from using the Commonwealth Fraud Risk Profile as a reference point, which provides an overview of common risk areas and mitigations across Commonwealth entities. Commonwealth officials can request a copy of this resource at info@counterfraud.gov.au.

The first step in the risk assessment process, as prescribed in AS/NZ ISO 31000-2018, is to establish the context of the function or program being assessed through communication and consultation. This involves understanding the business processes and procedures associated with these functions such as:

- the prescribed process to receipt goods or services and pay suppliers’ invoices

- the procedure followed to verify the identity of an individual or entity

- the methods to assess the eligibility of an individual or an entity to receive a payment

- the process to evaluate tenders submitted by potential suppliers of goods and services to an entity

- the standard operating procedure to approve and process pay increments to an entity’s employees.

By understanding these business processes and procedures it is possible to identify the fraud risks which may be inherent in these pathways.

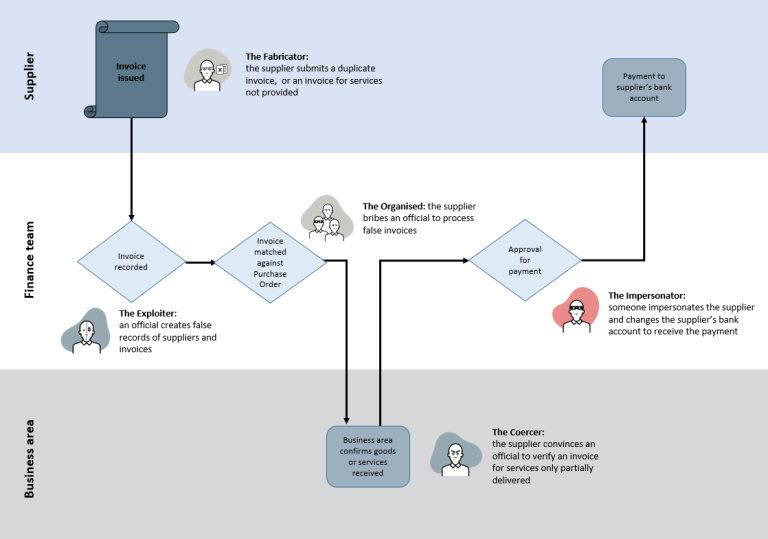

The diagram illustrates where fraud risks in an invoice payment process might be identified using Fraudster Personas.

- Step 1 - Supplier invoice issued (This part of the process could be targeted by The Fabricator who submits a duplicate invoice, or an invoice for services not provided)

- Step 2 - Finance team invoice recorded (This part of the process could be targeted by The Exploiter who creates false records of suppliers and invoices)

- Step 3 - Finance team invoice matched against purchase order (This part of the process could be targeted by The Organised who bribes an official to process false invoices)

- Step 4 - Business area confirms goods or services received (This part of the process could be targeted by The Coercer who convinces an official to verify an invoice for services only partially delivered)

- Step 5 - Finance team approval for payment (This part of the process could be targeted by The Impersonator who impersonates a supplier and changes the supplier’s bank account to receive the payment)

- Step 6 - Payment to supplier’s bank account

End of alternative text

Annex B provides an example of a more complex hypothetical government program, and illustrates how to combine business process mapping and Fraudster Personas to identify fraud risks.

There are a number of approaches that can be used to establish the context and identify fraud risks inherent in an entity’s functions. The choice of approach will depend on a range of factors, such as size and complexity of an entity’s functions, the geographical distribution of the entity’s workforce and functions, and time and resourcing constraints. Regardless of the approach taken, it’s important to identify and consult with representatives from the business unit(s) being assessed and any additional subject matters experts who may contribute to the identification of risks.

The following is a non-exhaustive list (in no particular order) of suggested approaches to establish the context and identify inherent fraud risks:

- Conduct interviews with senior executives responsible for corporate functions or externally facing programs which may carry inherent fraud risks. While these interviews should be structured around a set agenda, time should be allowed for exploration of topics. Annex C provides a guide on the matters to be covered in these interviews.

- Independently assess select processes and procedures, including a review of documentation and interviews with relevant personnel.

- Conduct a fraud risk survey using a questionnaire tailored for the entity’s business units or operational functions being assessed.

- Run a facilitated workshop approach involving the input of staff from the business unit being assessed. This approach can involve structured techniques such as business process mapping, flow charting or operational modelling. This is particularly useful when identifying fraud risks in the design phase of an externally facing government program.

- Conduct hypothetical scenario workshopping, where relevant stakeholders consider plausible methods of potential fraudsters.

- Examine fraud intelligence, previous fraud risk assessments, the results of fraud investigations, or consider case studies from other entities (this should not necessarily be restricted to Commonwealth entities).

Tip: Another approach that can help identify how someone would target a function or program, or get around a control is the ‘ABCD’ method:

- Actors – Who are the actors involved? For example, recipients, staff, service providers.

- Benefits – What benefits would they gain by committing fraud?

- Controls – What controls would they encounter?

- Determined adversary – How would a determined adversary deliberately find a way around controls to gain the benefit?

4.1.1 Describing fraud risks

An effective method for describing fraud risk is to consider the ‘Actor, Action and Outcome’. The level of detail is important when describing fraud risks. Without sufficient detail it becomes difficult to consider the factors (i.e. actors and actions) that contribute to the fraud risk and how fraud controls will specifically address these contributing factors.

- Actor – who is the active agent?

- Action – how do they act to commit fraud?

- Outcome – what is the result or intention?

A Fraud Control Officer should use their judgement in striking a balance between capturing sufficient detail and documenting a manageable number of fraud risks. This could be achieved by combining similar risks and clearly documenting the various contributing factors (actors and actions).

Furthermore, fraud risk descriptions can vary across different levels of risk assessment. For example, the ‘Actor, Action, Outcome’ approach may not be appropriate when describing fraud risks in an enterprise-level fraud risk assessment. This is due to numerous actions and methods being considered at this level.

See Information Sheet – Element 1: Fraud and corruption risk assessments for advice on describing fraud and corruption risks at the enterprise level.

Annex D provides a list of key data points that can be captured when identifying and describing a fraud risk.

Tip: An example of a poorly defined fraud risk from the invoice payment process provided in the invoice payment process above would be:

- “Fraud in the invoice payment process”

The following are more accurately defined fraud risks from the same example:

- “A service provider (Actor) submits a falsified invoice (Action) to receive a payment for services not provided (Outcome)”

- “A service provider (Actor) coerces an official to approve and/or process a falsified invoice (Action) to receive a payment for services not provided (Outcome)”

- “An official (Actor) manipulates the finance system (Action) to divert an invoice payment to their own bank account (Outcome)”

An important consideration when analysing a fraud risk is the nature, extent and effectiveness of fraud controls. You may be analysing a new risk for which no controls have been developed or implemented, or an existing risk with controls that may have known vulnerabilities. The effectiveness of any existing controls can have a direct influence on the likelihood of fraud risks being realised (see Section 4.2.1).

This step in the fraud risk assessment process requires input from the business unit(s) being assessed, and any additional subject matters experts who may add value to the process. This step can be conducted in a workshop setting or structured discussion and may also incorporate the fraud risk identification step described in Section 4.1. However, for large, complex programs or functions it may be more suitable to have separate workshops or discussions for these steps in the risk assessment process.

Refer to the Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre’s fraud control catalogue for help with identifying different types of fraud controls.

The following questions can assist to identify what controls are currently in place or what controls might be considered when treating fraud risks (see Section 4.4):

- What type of managerial oversight exists?

- How do you verify the evidence submitted by an applicant?

- Do you have any data matching in place?

- Who makes the final decision and are there automated workflows for decision making?

- What fraud detection controls are in place? Should there be more when considering rapid technological changes?

- Can someone lodge a tip-off or complaint?

- Are there any system audit logs?

- Are relevant policies and procedures in place and up to date, including those for the management and exercise of delegations and decision making?

Tip: The Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre has found that entities often overestimate the effectiveness of their controls. Applying a sceptical mindset to controls and adopting the mindset of a determined fraudster can help in considering whether a control might be overridden or avoided.

Annex F provides guidance on the categories of controls used to treat fraud risks and how to measure their effectiveness.

If conducting a risk assessment in line with AS/NZ ISO 31000-2018, the analysis of fraud risks involves estimating the ‘likelihood’ and ‘consequence’ of the individual risks. A risk analysis matrix can then be used to match the combination of likelihood and consequence to provide an estimation of the current risk rating.

Annex E provides an example of a risk analysis matrix.

Tip: An alternative to using a risk analysis matrix to estimate the level of fraud risk is applying a scoring system against the estimation of likelihood and consequence which will provide a fraud risk score. The Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre has developed a Fraud Risk Assessment Template that uses such a system. Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre has developed a Fraud Risk Assessment Template that uses such a system.

Annex D provides a list of key data points that can be captured when analysing a fraud risk.

4.2.1 Estimating the likelihood of fraud

When determining the likelihood of fraud, one should consider both the probability (what is the chance of the fraud taking place) and frequency (the number of fraud incidents that can be expected). This must be done while taking in account the nature, extent and effectiveness of fraud controls. There are a number of other factors which can be considered including:

- the volume of financial transactions associated with a business function or payment program

- the range and type of access points to the business function or payment program and the extent to which these are automated

- the nature and quantum of the potential benefit to the fraudster

- previous history of fraud against the business function or payment program (is there a known organised crime threat?)

- public awareness of an eligibility payment program

- time scales (for example, what is the duration of the function or program).

An entity’s risk management framework should provide guidance on how to quantify the likelihood of a risk occurring.

4.2.2 Estimating the consequence of fraud

When determining the consequence of fraud, once should consider both the duration (time before fraud is prevented, detected or disrupted and the impact (the potential severity of the fraud). An entity’s risk management framework should provide guidance on estimating the consequence of fraud risks, should they be realised. The consequence of fraud is commonly measured by the level of financial loss that might occur as the result of a single incident, or through cumulative losses from several incidents over a period of time. Government entities generally lose between 3% and 5.95% of their spending to fraud and related loss, based on international estimates.

Fraud incidents also involve non-financial consequences that should be considered:

- Human impacts – fraud can be a traumatic experience that often causes real and irreversible impacts for victims, their families, carers and communities. Some examples of human impacts to consider include:

- Health effects for persons relying on services

- Identity theft

- Reduced physical safety

- Reduced staff welfare and morale.

- Compromised outcomes – fraud undermines the government’s ability to deliver services and achieve intended outcomes. Some examples of compromised outcomes include:

- Failing to meet program objectives

- Loss of services

- Poor customer or client experience.

- Reputational damage – fraud can result in an erosion of trust in government and industries, and lead to a loss of international and economic reputation. Some examples to consider include:

- Erosion of trust in government and partners

- Reduced employee morale

- Degrading of reputation.

- Industry impacts – fraud can result in distorted markets where fraudsters obtain a competitive advantage and drive out legitimate businesses. Some examples to consider include:

- Market distortion and unfair competition

- Demands on community services by victims

- Cost of compliance with increased regulation.

- Environmental damage– fraud can lead to immediate and long-term environmental damage through pollution and damaged ecosystems and biodiversity. Some examples to consider include:

- Increased pollution

- Reduced biodiversity

- Disturbed ecological balance.

- Security compromise – fraud can be a direct threat, or enable threats, to security, such as by funding serious crimes including terrorism. Some examples to consider may include:

- National defence or security

- International relationships

- Organisational or information security

- Funding source for other serious crimes.

- Business costs – the costs for dealing with fraud go well beyond the direct financial loss and can include investigation and response costs as well as potential restitution. Some examples to consider include:

- Management and Investigation costs

- Restitution or remediation costs

- Elevated insurance premiums

- Drain on criminal and civil justice activities.

Once an entity’s fraud risks have been rated in the analysis step, these risks are evaluated against the entity’s risk appetite and tolerance, which can be defined in an entity’s risk management policy and framework. The nature of an entity’s business functions will determine its tolerance to fraud risks; for example, large service-delivery entities may have a greater tolerance to fraud risk owing to a higher level of risk inherent to their functions and programs. On the other hand, entities with responsibility for regulatory compliance and law enforcement will likely have a much lower tolerance with regards to fraud and corruption risks.

Risk tolerance is not a static determination. It will depend on the circumstances of individual programs and other objectives beyond mitigating fraud risks.

Annex E provides an example of a risk management action table which can be prescribed in an entity’s risk management framework and can reflect an entity’s risk appetite and tolerance. The table provides instructions for fraud risk owners on the actions required for different levels of fraud risk. Officials should refer to their own entity’s risk management action table when evaluating fraud risks.

It is important that the evaluation of fraud risks involves input from fraud risk owners with sufficient seniority to be able to consider the cost of countering fraud against the entity’s risk tolerance. An effective risk evaluation process can assist fraud risk owners in deciding a number of possible options, such as:

- avoiding or terminating the fraud risk by deciding not to start or continue with the activity that gives rise to the risk

- accepting a fraud risk that is within the entity’s risk tolerance and appetite by maintaining existing controls and monitoring the risk

- accepting a fraud risk that is outside an entity’s risk tolerance and appetite by informed decision, for example it has been determined that:

- the anticipated benefits of the activity outweigh the consequences of the risk, or

- the costs of additional treatment, or the timeframes to implement additional treatments, would have a negative impact on the outcomes of an essential activity

- undertaking further risk analysis, such as conducting an audit or test existing controls (refer Section 5.3)

- treating the fraud risk to an acceptable residual (or target) level by reducing the likelihood and / or the consequences (see Section 4.4).

Annex D provides a list of key data points that can be captured when evaluating a fraud risk.

When treating a fraud risk to achieve an acceptable residual (or target) level of risk, the options available might be to enhance existing controls or to introduce new and more effective controls. As indicated in Annex F, these controls can be grouped under fraud prevention, detection or response.

Tip: Treating likelihood or consequence?

Most fraud controls are designed to reduce the likelihood of fraud, but some can be targeted at reducing the consequences of fraud. For example, reducing the maximum amount of an eligibility payment can reduce the financial consequences of a fraudster who is able to successfully find a way around controls designed to reduce the likelihood of the fraud risk occurring.

The Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre has developed a fraud control catalogue as a useful resource for considering additional controls or enhancing existing controls. The fraud control catalogue provides:

- a summary of each control

- specific examples of each control

- an explanation of the purpose of each control

- suggested ways of measuring the effectiveness of each control

- vulnerabilities to consider for each control (email info@counterfraud.gov.au for this information)

- dependencies (links to other controls that entities can consider within a broader control environment).

When considering new controls, or addressing gaps and vulnerabilities in existing controls, a co-design approach will achieve greater engagement and buy-in from stakeholders. As with fraud risk evaluation, it is important to get input from fraud risk owners with sufficient seniority to consider the cost of controls against the risk exposure.

Annex G outlines the ‘SMART’ principle as an example of what to consider when co-designing controls with stakeholders.

Tip: Fraud risk owners can sometimes encounter problems with fraud control owners responsible for developing, implementing and maintaining fraud controls relating to their risks. This may be because a control owner is experiencing staffing or funding constraints or they lack the requisite expertise. In these circumstances the Fraud Control Officer can assist through:

- fostering productive linkages between parties responsible for fraud control,

- providing expert advice to stakeholders, or

- seeking strategic support from the Senior Fraud Officer to formulate solutions to impediments at the operational or program level.

See Information Sheet – Element 2: Fraud and corruption control plans for advice on developing functional control plans that deal with the fraud and corruption risks identified.

4.4.1 Information and data sharing in fraud controls

Australian Government entities are encouraged to explore data sharing opportunities when designing new fraud controls. Australian Government entities hold vast amounts of data and information and unlocking and sharing data and information can be a powerful tool to prevent, detect and respond to fraud.

Example fraud risk 1:

“A grant applicant (Actor) provides false accreditations (Action) to be eligible to receive a payment (Outcome).”

The entity administering the grant program treats this risk by collecting data from the accreditations board to validate eligibility. Once identified, the entity also disrupts this type of fraud by sharing information under Part VIID of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) about fraudulent applicants with other grants programs.

Example fraud risk 2:

“A social welfare recipient (Actor) provides misleading information on their income and asset status (Action) to be eligible to receive a welfare payment (Outcome).”

Under a Memorandum of Understanding between the Australian Transaction Reporting and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC) and Services Australia, specific financial transaction and financial reporting data is shared. The AUSTRAC data match will enable Services Australia to identify social welfare recipients who may not have appropriately disclosed their correct income and asset status.

Refer to the Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre’s Data Sharing Pilots Leading Practice Guide for practical advice and principles to consider when commencing data or information sharing activities.